New research finds that it is not how many species you have, it is what they ‘do’ in an ecosystem that matters.

The international research team, led by UC Riverside geology professor Andy Ridgwell, looked at the evolutionary recovery of marine plankton after the dinosaur-exterminating asteroid hit Earth 66 million years ago.

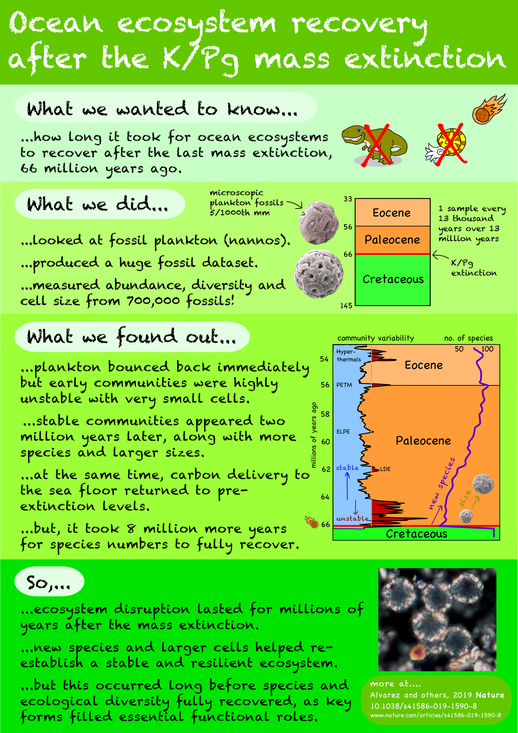

The team produced an unprecedented record of the ocean’s recovery in the 13 million years that followed this event, measuring the abundance, diversity and cell size from over 700,000 fossils. Their findings are being published this week in Nature.

When many of the plankton went extinct, it eliminated much of the food production at the base of the marine ecosystem and crippled important ocean functions, such as the delivery of carbon to the deep sea, which is a critical control on atmospheric carbon dioxide.

“Effectively, we are using the geological record of plankton recovery from mass extinction as a natural laboratory to teach us about the role of biodiversity and the functioning of ecosystems in general,” Ridgwell said.

Ridgwell said the surprising finding in this study was how little biological diversity was required for a fully functioning carbon cycle to be re-established. This took a mere 2 million years after the impact. However, the right pieces of the system have to be present for the cycle to renew. “It doesn’t appear to matter how many species you have, but rather, what the existing species do in the ecosystem,” Ridgwell said.

“What we see in the first 2 million years of recovery are new species evolving, dominating the ecosystem, then going extinct again,” Ridgwell said. “It’s like the Darwinian dice are being repeatedly rolled until a double-six is achieved.”

Once a stable ecosystem and functioning global carbon cycle is achieved, further species are added and ecological diversity begins to return. The team found that it took an additional 8 million years to ultimately re-establish a marine world as diverse as the one that existed prior to the impact.

The team, composed of researchers from universities in London, Bristol, and Frankfurt as well as UC Riverside, stressed that today’s marine ecosystem is just as dependent on the plankton at its base today as it was in the past. This study highlights the risks posed by diversity loss, which could result in highly unstable animal and plant communities, the loss of important ecosystem functions and long timescales of recovery.

"The more species and diversity that you have, the more redundancy you have in the system – like having a cloud backup for your key plankton. One reason to protect current global biodiversity is to retain this redundancy and reduce the risk of losing the last copy of a vital piece of the puzzle, and having the system collapse on you," Ridgwell said.

It is something to note, as the world watches the rapid bleaching and extinction of Australia’s 1,400-mile-long Great Barrier Reef. Corals in the reef are bleaching at an unprecedented rate, and as a key species in that ecosystem that creates the reef framework, the geological record suggests a very different and unstable ecosystem may replace it.